March 23, 2018

by Andy Saks, live auctioneer

A paddle raise is a powerful, effective way to boost donations at your fundraiser.

As a professional live auctioneer, I’ve built and delivered many paddle raises over the years. I wrote this article to help you learn from my successes (and mistakes), so your paddle raise scoops every available dollar, generating the highest returns for your efforts, and the most help for your organization.

Paddle raises and live auctions are two separate and distinct fundraising structures. They’re often run back-to-back at the same fundraiser, though you can (and I have) run one without the other if you think one structure is appropriate for your organization and the other isn’t.

Here’s the difference: a live auction asks donors to bid cash to win prizes (physical items, trips, experiences, etc.). Generally only one donor wins a particular prize, and it’s the donor who bids the highest amount for that prize.

In contrast, a paddle raise doesn’t include prizes at all. It asks donors to “raise your paddle” (or pieces of paper, or whatever item shows their donor number) to give a specific amount of cash to support the recipient’s organization as a whole, or to support a specific need within that organization.

Moreover, paddle raises commonly request donations on a scale of varying dollar amounts (say, $10,000, $5000, $2500, $1000, $500, $100) to give donors of varying financial means donation levels within their reach. There’s no limit to the number of donors who can donate at any level—indeed, the more donors you generate at each level, the better—and generally no donor receives any tangible return for their donation. Donors give purely to support the efforts of the recipient.

Paddle raises are often called “raise your paddle,” “fund a cause” or “fund the need” events. However, there’s a subtle-but-important distinction: a “paddle raise” or “raise your paddle” event is a more general name for this category of donations-without-prizes fundraising, while “fund a cause” or “fund the need” events assign a distinct, specific need to each dollar level requested. (See Tip 2 below.)

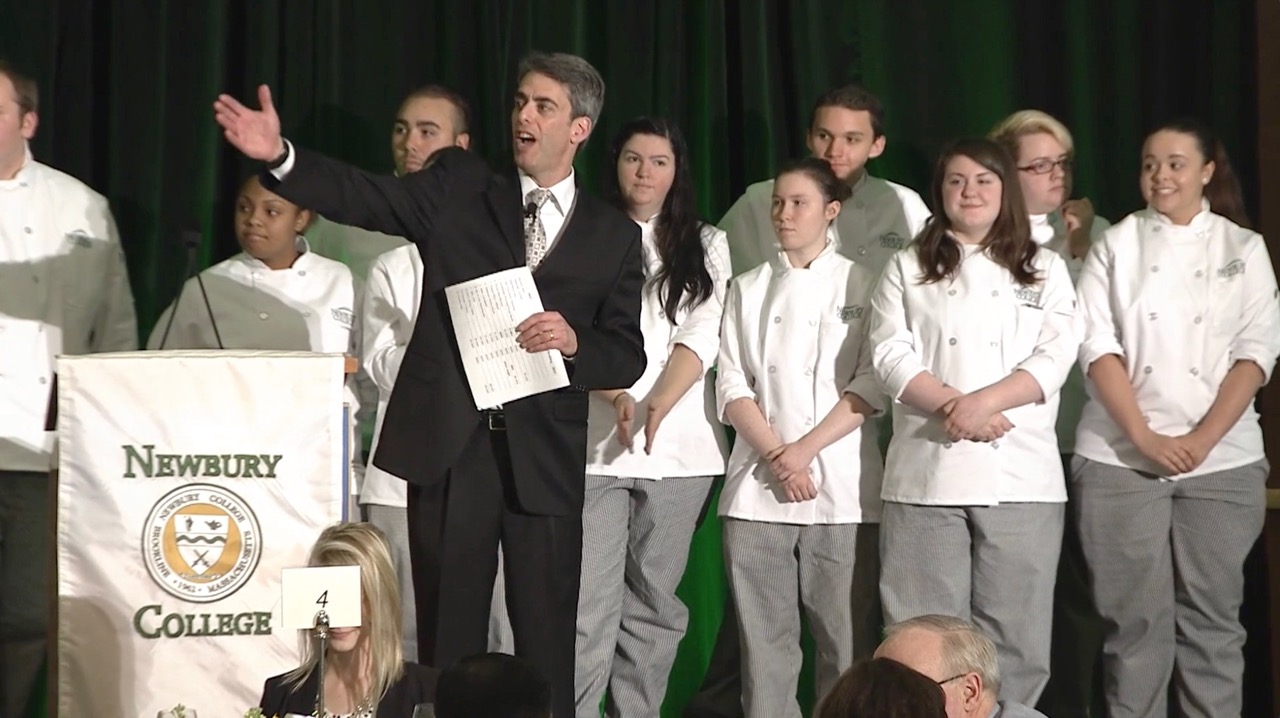

Confused yet? Watching a paddle raise might help. Here’s a paddle raise I ran for Newbury College’s fundraiser at the Boston Seaport Hotel (that’s me in the suit!):

And another one, for the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, at Boston’s Fairmont Copley Hotel (still me in the suit!):

As you can see, paddle raises feel more serious, direct and urgent than fundraising games and auctions.

So how do you run a successful paddle raise? As with the rest of your fundraiser, it’s all in the execution. Running a well-designed, well-delivered paddle raise can significantly boost your donations; running a clunky, awkward one can squander a prime donation opportunity you’ll never get back. So here are 10 tips to help you build it, run it, and raise more from it:

Chances are, you’ve got a few donors at your fundraiser with deep pockets, a few more with medium pockets, and many with relatively-shallow pockets.

To give all donors the opportunity to donate their maximums, create a series of 5-7 different dollar amounts, or “levels.”

STEP 1: SET YOUR HIGHEST DONATION LEVEL. Make it as high as you possibly can while still ensuring at least one generous donor will reach it. In my experience, that level is usually $5000, $10,000 or $20,000. For your organization, it might be $100 or $1,000,000. (Remember, just one $20,000 donation is worth forty $500 donations, so even if only one person will donate at your top level, let them!)

STEP 2: SET YOUR LOWEST DONATION LEVEL. The amount should be low enough that almost all donors would be comfortable giving it. For my clients, this level is almost always $100.

STEP 3: SET 3-5 DONATION LEVELS IN BETWEEN. These should represent a logical series of “steps” between your highest and lowest level, each step approximating what donors at a specific level of financial ability might give. For example, imagine your top level is $5,000 and your bottom level is $100. People who won’t donate $5,000 probably won’t donate $4,000, but might see $2,500 as a “bargain,” so make that your next level. Those who can’t reach $2,500 might jump at $1,000, so add that level next. Keep going, and you’ll probably end up with levels like these: $5,000, $2,500, $1,000, $500, $250 and $100.

STEP 4: ADD A “GIVE WHAT YOU WANT” LEVEL below your lowest level, for donors with their own specific, fixed donation amount in mind, like $65; otherwise you’ll miss them!

Next, match each donation level to a specific, unique, urgent need in your organization, so your donors feel their donations will make a big, immediate, tangible difference.

These needs are generally everyday, concrete expenses that aren’t sexy, but are crucial to keeping the organization serving its beneficiaries.

Here are some examples of expenses funded in paddle raises I’ve run:

TEEN LACROSSE NONPROFIT: Buying a van to travel to away games; panting the white lines on the lacrosse field; purchasing new uniforms and equipment; covering travel expenses for overnight college visits; renting gym space for practices; hiring coaches.

YMCA CHAPTER: Providing after-school care and activities; sending special-needs children to summer camp; covering YMCA memberships and admissions to cancer wellness program; purchasing private swim lessons.

COLLEGE CULINARY ARTS DEGREE PROGRAM (see Newbury College video above): Funding a semester-long internship; purchasing required textbooks, culinary uniform and knife set; paying registration fee for ServeSafe exam. (Each donation covered these items for one student.)

How do these organizations match their needs and donation levels so perfectly? They didn’t (and you don’t have to either!). There’s some sleight-of-hand involved in “adjusting” your needs to make them match your levels. You can combine smaller needs together at one level, split bigger needs into many levels, multiply or divide needs to serve one or many recipients, group needs by theme, location, timing, age or other category, really anything to make the dollars you need roughly match the levels you’ve created.

That’s me on stage running a paddle raise in Boston. If you see this at YOUR paddle raise, nice job!

Common sense says you start with the lowest level first and move up, yes?

Actually, it’s the opposite. Start with your highest level and move down.

Here’s why: imagine you start by asking everyone for your lowest level, $100. Every donor raises their paddle,. Some think, “Wow, I was ready to give much more. What a deal!”

Next, you ask for $250. But everyone in the room has already donated. Now you want them to donate again, and much more this time? No one donates, and some donors look irked. Good luck asking for $500, or $5,000.

In contrast, starting high and moving low allows your biggest donors to shine first, and each successive (lower) donation level now seems reasonable to your budget-conscious donors, making them more likely to “stretch up” to reach it.

So what’s “keep it to yourself?” A reminder not to tell your audience in advance what you’re donations levels are before you get to each one. Imagine a donor who’s ready to donate $150. If they know your last level is $100, they’ll wait for your $100 level to donate; if they think $250 may be your last level, they just might donate $250.

One of the most powerful ways to move donors to donate is having someone directly involved in that level’s need stand up, take the microphone, and advocate for it.

What kind of speakers make the best advocates? Try one of these:

PAST / CURRENT RECIPIENT who explains how this item or service changed (or will change) their world.

ORGANIZATION MEMBERS directly connect to this need, who explains why it’s worthy and how funding it helps recipients.

PAST DONORS to this need talk about what providing this help meant to them.

Advocates are most successful when they keep speeches short (aim for one minute or less), direct, honest, personal, and focused on their own first-hand experience or knowledge. (No begging, goading, threatening, or other tactics likely to alienate donors.)

Nothing kills your paddle raise momentum faster than asking for a donation level, then watching heads swivel as everyone looks for raised paddles and none appear.

To avoid that, designate a “plant” donor for your highest 1-3 donation levels. Plants are usually your most generous, dependable donors, the folks who are always eager to help. Ask them BEFORE your fundraiser to commit to donating at a certain level, and make them promise to raise their paddle when you ask for donations at that level.

Once other high-dollar donors see your plant donate, they’re more likely to donate as well. That starts your paddle raise off with a “win” that encourages subsequent donors, and will likely raise your total donations significantly.

NOTE: If your preferred plant can’t be there, you can still use them as a plant. Just have the person running your paddle raise announce the plant’s donation, i.e. “I’m excited to announce that [name] has generously donated [$XXX]. Thank you!”

Remember when I said it’s all in the execution? Here are some examples from my own scripts on how to explain paddle raise details to your donors:

1. Explaining why it’s an opportunity for them:

“Now we know we’ve asked a lot of you tonight, and you’ve given generously, and we deeply appreciate it. But I suspect that many of you might still feel you haven’t made your statement of how much [organization] means to you personally. This paddle raise is your last chance to make that statement. Folks, if you’ve been holding back tonight, if you haven’t quite found your moment yet, this is it!”

2. Explaining how your paddle raise works:

I’ll introduce six donation levels. For each one, I’ll share the specific, urgent challenge you’ll fund by donating at that level. After I do, if you’d like to donate at that level, just raise your paddle. A volunteer will record your donation amount. That’s all there is to it.”

3. Explaining how a given donation level will be used:

“As you may know, transportation is [organization]‘s largest single expense, and the smartest way to control that expense is to stop renting and start owning. So [organization] is asking you to make a [$XXX] donation to help underwrite the purchase of two passenger vans to help transport its youth, junior, and high school teams to a variety of games, practices, and competitions. They want to compete in some great events this year, like [examples]. These vans mean the difference between competing and not competing to these events.”

Run your paddle raise toward the end of your fundraiser, after your meals are served, your auctions are closed, your games are played, and your fundraiser is close to wrapping up.

This is the moment when attendees are likely most receptive to your appeal. They’re fed (and maybe buzzed!), relaxed, connected to your organization, focused on your beneficiaries, and open to considering a direct appeal that might seem pushy if you asked earlier in your event. Running it after your auctions and games end also lets donors calculate how much money they have left to spend, which encourages them to spend it.

Moreover, as with any activity in your fundraiser that demands everyone’s focus, your paddle raise suffers when it competes for the donors’ attention with any other activities in the room. This includes food service (with moving wait staff, clanging silverware, and a desire to focus on eating and table mates), entertainment from your band / DJ / entertainers, walk-up bar service, silent auction bidding, and so on.

Running these activities alongside your paddle raise tells donors you don’t care if they listen. Many will take your cue and tune into something else. So stop ALL other activity, keep the room quiet, and let your donors calmly consider your “ask” without distractions.

For this paddle raise, I brought ALL the young chefs in Newbury College’s School of Culinary Arts on stage, and their presence raised donations!

For most people, speaking to an audience is scary, and asking an audience for money is terrifying. So people who run paddle raises are tempted to wiggle out of the part where they actually ask for the money, reasoning, “Everyone knows I want them to donate. Do I have to ask them?”

Yes, you do. It’s a fundraiser. Remember all that work your team did to make it happen? You did it to raise funds. Now it’s time to ask for those funds, clearly and directly.

How do you ask? I use a “no-frills” approach. After a donation level has been fully explained, I say:

“If you’d like to donate this amount, please raise your bid number now.”

That’s it. Just ask. Then stay silent for at least ten seconds, and give your donors the chance to do their thing.

Don’t get clever and make your “ask” funny, sad, weird, or anything else. Just ask. If you laid your groundwork well, I bet you’ll discover your donors are eager to say “yes.”

Imagine doing everything suggested above, raising a record amount of money, then collecting only half of it. That can happen when no one accurately tracks donations from a paddle raise. Paddles get raised and lowered quickly, and donations get missed. Donors you approach after your event may not remember what they promised, so they donate less, or nothing.

Ensure you collect what you expect with a few simple steps:

Now that your donors have donated, thank them right then and there with a small physical token of your appreciation, like a commemorative coin, patch, badge, note, or flower. They’ll keep it as an ongoing reminder of how much they mean to you, and seeing them receive it will entice other attendees to donate.

I hope you find these tips helpful, and invite you to share your own tips and stories. And I hope your next paddle raise is a big success!

And since you’ve read this far, enjoy another paddle raise video, for the Riverbend School at the Sheraton Framingham Hotel near Boston:

Tags: live auctioneer, paddle raise

Add your comment